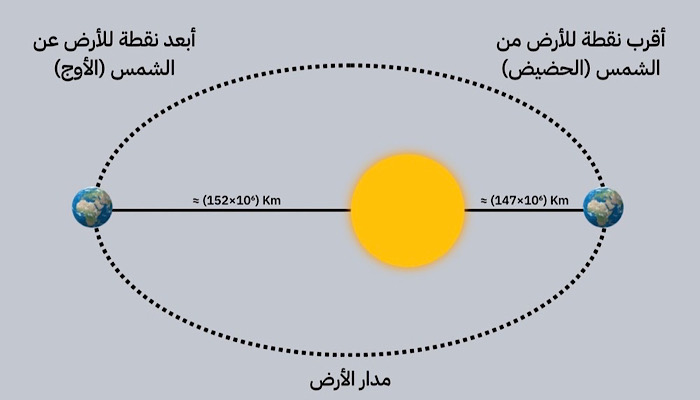

Muscat: Earth will reach its closest point to the Sun on Saturday, January 3, 2026 in its annual orbit, a position known astronomically as the perihelion. At that moment, the distance between the centers of Earth and the Sun will be approximately 147.1 million kilometers, or about 0.9833 astronomical units.

Ibrahim bin Mohammed Al-Mahrouqi, Vice Chairman of the Oman Astronomical and Space Society, explained that this astronomical event is a natural annual phenomenon that occurs at the beginning of January each year. It takes place just under two weeks after the winter solstice, due to the slightly elliptical shape of Earth’s orbit around the Sun. The orbit’s eccentricity is about 0.0167, a minor deviation from a perfect circle, in accordance with Kepler’s laws of planetary motion.

He noted that Earth reaches its farthest point from the Sun, known as the aphelion, in early July each year, when the distance increases to about 152.1 million kilometers. The difference between aphelion and perihelion is roughly 5 million kilometers.

Al-Mahrouqi emphasized that Earth’s proximity to the Sun has no direct impact on temperature or seasonal changes. The true and primary cause of seasonal variation is the tilt of Earth’s rotational axis, which is inclined at about 23.5 degrees relative to the plane of its orbit around the Sun—not the Earth-Sun distance.

He elaborated that Earth does not orbit the Sun in an upright position; rather, it is tilted. This tilt causes the angle of sunlight to vary throughout the year. In summer, the Sun’s rays strike the Northern Hemisphere more directly, making the Sun appear higher in the sky, lengthening daylight hours, and concentrating solar energy over a smaller area leading to warmer temperatures. In contrast, during winter, sunlight arrives at a slant, the Sun appears lower in the sky, daylight hours are shorter, and solar energy is spread over a larger area and passes through more of the atmosphere resulting in cooler temperatures.

He added that the effect of the changing Earth-Sun distance is relatively minor compared to the impact of axial tilt. The variation in distance is only about 3% from the average of 149.6 million kilometers, and the slight increase in solar radiation at perihelion about 7%

occurs during the Northern Hemisphere’s winter, partially offset by the shorter duration of winter due to Earth’s increased orbital speed at perihelion, again in line with Kepler’s laws.

This effect is more noticeable in the Southern Hemisphere, where summers tend to be slightly warmer and winters slightly milder compared to the Northern Hemisphere. However, this difference remains limited and is not comparable to the dominant influence of Earth’s axial tilt, which remains the decisive factor in the cycle of seasons.

The Vice Chairman concluded by emphasizing that such celestial events offer a valuable opportunity to promote astronomical awareness, correct common scientific misconceptions, and highlight the precision and harmony of the cosmic system that governs the motion of celestial bodies.